"Tsech'i of Nan-po was travelling on the hill of Shang when he saw a large tree which astonished him very much. A thousand chariot teams of four horses could find shelter under its shade. "What tree is this?" cried Tsech'i."Surely it must be unusually fine timber." Then looking up, he saw that its branches were too crooked for rafters; and looking down he saw that the trunk's twisting loose grain made it valueless for coffins. He tasted a leaf, but it took the skin off his lips; and its odor was so strong that it would make a man intoxicated for three days together. "Ah!" said Tsech'i, "this tree is really good for nothing, and that is how it has attained this size.

A spiritual man might well follow its example of uselessness."

A certain carpenter Shih was travelling to the Ch'i State. On reaching Shady Circle, he saw a sacred li tree in the temple to the God of Earth. It was so large that its shade could cover a herd of several thousand cattle. It was a hundred spans in girth, towering up eighty feet over the hilltop, before it branched out. A dozen boats could be cut out of it. Crowds stood gazing at it, but the carpenter took no notice, and went on his way without evencasting a look behind.

His apprentice however took a good look at it, andwhen he caught up with his master, said, "Ever since I have handled an adzein your service, I have never seen such a splendid piece of timber. How wasit that you, Master, did not care to stop and look at it?"

"Forget about it. It's not worth talking about," replied his master. "It's good for nothing. Made into a boat, it would sink; into a coffin, it would rot; into furniture, it would break easily; into a door, it would sweat; into a pillar, it would be worm-eaten. It is wood of no quality, and of no use. That is why it has attained its present age."

When the carpenter reached home, he dreamt that the spirit of the tree appeared to him in his sleep and spoke to him as follows: "What is it you intend to compare me with? Is it with fine-grained wood? Look at the cherry-apple, the pear, the orange, the pumelo, and other fruit bearers? As soon as their fruit ripens they are stripped and treated with indignity. The great boughs are snapped off, the small ones scattered abroad. Thus do these trees by their own value injure their own lives. They cannot fulfil their allotted span of years, but perish prematurely because they destroy themselves for the (admiration of) the world. Thus it is with all things.

Moreover, I tried for a long period to be useless. Many times I was in danger of being cut down, but at length I have succeeded, and so have become exceedingly useful to myself. Had I indeed been of use, I should not be ableto grow to this height. Moreover, you and I are both created things. Have done then with this criticism of each other. Is a good-for-nothing fellow in imminent danger of death a fit person to talk of a good-for-nothing tree?"

When the carpenter Shih awakened and told his dream, his apprentice said, "If the tree aimed at uselessness, how was it that it became a sacred tree?"

"Hush!" replied his master. "Keep quiet. It merely took refuge in the temple to escape from the abuse of those who do not appreciate it. Had it not become sacred, how many would have wanted to cut it down! Moreover, the means it adopts for safety is different from that of others, and to criticize it by ordinary standards would be far wide of the mark."

Tsech'i of Nan-po was travelling on the hill of Shang when he saw a large tree which astonished him very much. A thousand chariot teams of four horses could find shelter under its shade. "What tree is this?" cried Tsech'i."Surely it must be unusually fine timber."

Then looking up, he saw that itsbranches were too crooked for rafters; and looking down he saw that the trunk's twisting loose grain made it valueless for coffins. He tasted a leaf, but it took the skin off his lips; and its odor was so strong that itwould make a man intoxicated for three days together.

"Ah!" said Tsech'i,"this tree is really good for nothing, and that is how it has attained this size. A spiritual man might well follow its example of uselessness."

In the State of Sung there is a land belonging to the Chings, where thrive the catalpa, the cedar, and the mulberry. Such as are of one span or so in girth are cut down for monkey cages. Those of two or three spans are cut down for the beams of fine houses. Those of seven or eight spans are cut down for the solid (unjointed) sides of rich men's coffins. Thus they do notfulfil their allotted span of years, but perish young beneath the axe. Such is the misfortune which overtakes worth. For the sacrifices to the River God, neither bulls with white foreheads, nor pigs with high snouts, nor men suffering from piles, can be used. This is known to all the soothsayers, for these are regarded as inauspicious. The wise, however, would regard them as extremely auspicious (to themselves).

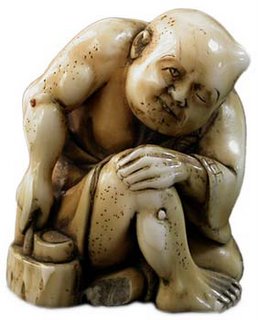

There was a hunchback named Su. His jaws touched his navel. His shoulders were higher than his head. His neck bone stuck out toward the sky. His viscera were turned upside down. His buttocks were where his ribs should have been. By tailoring, or washing, he was easily able to earn his living.By sifting rice he could make enough to support a family of ten. When orders came down for a conscription, the hunchback walked about unconcerned among the crowd. And similarly, in government conscription for public works, his deformity saved him from being called. On the other hand, when it came togovernment donations of grain for the disabled, the hunchback received as much as three chung and of firewood, ten faggots. And if physical deformity was thus enough to preserve his body until the end of his days, how much more should moral and mental deformity avail!

January 02, 2006

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment